Ye Olde Monolith

09 August 2016 Comments off

Reading time:

16 minutes

Word count:

3537

As a professional software engineer, you probably have encountered an architectural stumbling block known as a MONOLITH#1. A monolith is essentially a single tier application in enterprise architecture. Forget about the traditional break-down of Java EE application, where they break down an Uber-WAR file into presentation, business-logic and database tiers. That is just gloss over our very eyes, a single WAR file deployed to an application server is, at best, a monolith.

In my contracting experience, I have witnessed many types of monoliths at various stages of software development lifecycle. Unfortunately, I have been towards to the latter end of SDLC where the monolith application is already in maintenance mode or has been reiterated several times. It is the nature of contracting that the conditions of bit rot have already been set and they are irreversible.

A monolith has the following characteristics:

- The application code is generally unfathomable, because the modules are inextricably interlinked making analysis absurdly complex.

- The time of development cycles gradually increase through each milestone release.

- There is a vast swathe of code and modules. I would say over 500,000 lines of code and over 250 modules is de-rigour.

- The ratio of unit test classes to regular code is alarmingly very low, sometimes much less than 5%.

- Usually there are only one or two persons in the organisation who has any clue how the whole monolith hangs together.

- There is a culture of resistance to change. Sometimes that culture is political.

- People have passed through the eye of the needle many times over.

Initialisation

How do MONOLITHS come to being? Who is responsible? I have my suspicions about the origin. In my experience, they are started when a business generates and builds software from a brownfield #2 environment.

seems to hang on in all shape and all form.

How does a monolith actually start? It starts with basic requirement or that appears to be fundamental and then deviates into the asylum from the beginning date. The weird thing is that it does not matter if you have average engineers or a crack team of skunk workers, with at least 10 years’ experience and, say, that each person had worked as technical architectural leaders in the past. Software, unfortunately, is very subjective. We have all opinions on the best framework, the best library and we are limited by the constraints we have in our knowledge at the time of the monolith’s conception.

Why do I call the initial conditions brownfield? Because there is rarely a case in a prototype or stareter version where we build everything from scratch. A monolith starts with a dependency like Java EE, if the code is written in Java. It will be different if your monolith is written in PHP, Python, Groovy, Scala or Ruby.

In the era before Agile, the monolith came to being through a Big Upfront-Design (BUFD), Project Initiation Document (PID) and New Enterprise Architecture Document (NEAD).

Here is an extract of old proposal document that I have:

Executive Summary:

What is UTD and why are we building it?

How is it being implemented?

When will it be delivered and what will be included?

Where are we now?

Summary and future development / roadmap

UTD Objective

“This new application will be a near real-time Trading Desk Add-On to provide consolidated single source of Trade Data in a format understandable by X-QuantLib Exposure Library (X-QEL). The contents of UTD will be updated upon trade lifecycle events and will be available via an API. Traders will be migrated from LEGACY-Y to UTD in progressive steps. UTD will be available across the Web and also Desktop profiles.”

From the above sample description, which was written in 2009, I have changed some terms in order to protect the innocent, you can see exacting business knowledge [jargon] is required#5. If I could have returned to this monolith in 2016 and re-examined this application, it would likely be still a monolith, and I doubt that I would find the original documentation that described the start of the journey. In fact, I have engaged in a few contracts and the client cannot longer lend their hands on the original BUFD.

Culture

A monolith is characterised by the culture that creates it. As soon as code is written, some say, you are already in a technical debt. In effect, writing code even with unit tests is like taking an option on the future outcome. A fully unit test harness is the guarantee reference and a promise to yourself that you might change the production code eventually. Moreover, if you know that code is just a prototype then you can afford to cut corners and deliver the fastest working example of the application that impresses the stakeholder.

The prototype that eventually grows into the ageing monolith rarely ever gets thrown away or restarted. There is an early day scenario where the majority of the application should be rebuilt from scratch, but because of business pressures like cost, time-to-market and finance, nobody ever does this. Over time the monolith keeps growing and stretching further into the distance.

After several Person-years this mountain of code keeps growing every day, every month and every year. Why? Because a monolith is nothing except a transformation of a viable business model, in other words as long the business can makes profit [or it thinks that it can] then it will self-sustain#7.

Monoliths to date are also a victim of software engineering trends. We can look at the technology and the libraries. The oldest Java monoliths, probably, were created long before the creation of Spring Framework, Guice and Context Dependency Injection. Some monoliths, therefore, were conceived when Java did not have annotations or even generics, which is pretty old. Even the best practice of the times change with time. By 2016, the J2EE design patterns are woefully past their sell-by date and I would also add action controllers written against Apache Struts version 1.0 to the mix.

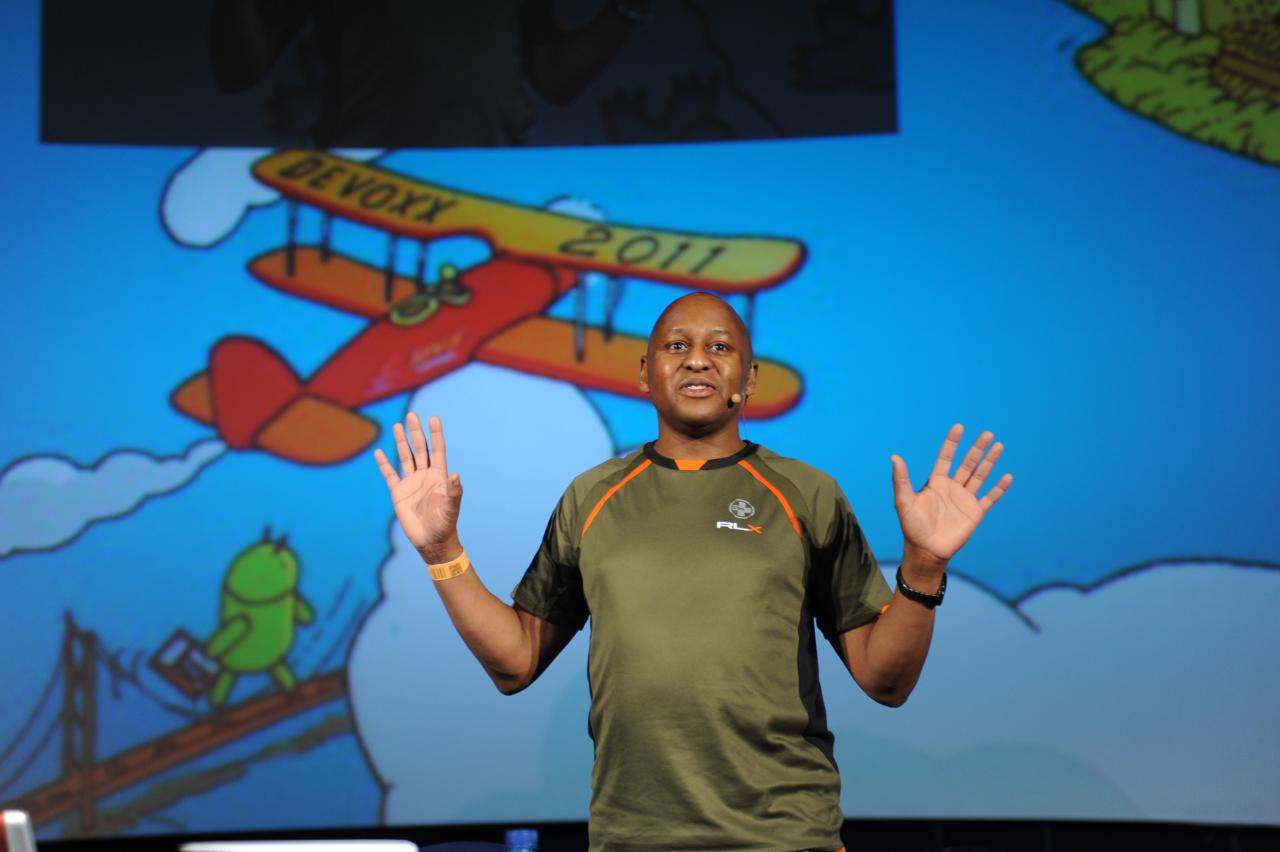

At best, the monoliths were never modularised or designed for best practice of components#3. Joe Nuxoll was one of the first people that ever heard who was pushing componentisation design and properties for software, unfortunately, Java the language never did get there.

Conway’s Law

Conway’s Law asserts that organisations are constrained to produce application designs that mirror their communication infrastructures. No matter how adaptive an organisation tries to break out beyond the law, the result always is unintended communication breakdowns between management, departments and silos; which all require resolution.

Unsurprisingly, monoliths will exhibit the structure of the people that created and also maintain them.

Staff turnover

A monolith is also affected by staff turnover. If new business team has an original idea of an application at the very beginning, after a few years the application’s direction will change. Because existing staff leave the business, move on to new projects and learning; and also original consultants and contractors leave the project, the arrow of development changes orientation as new people arrive. The new staff must learn new concepts and they rarely handed over in fashion that shows maximum knowledge transfer.

Undersell

I came across at least two monoliths in my time, which were the product of software houses. The monoliths were large and at least one of them was supremely huge by modern standards, because they factored in JavaScript and modern front-end libraries to solve the Single Page Application paradigm #4.

Please stay tuned!

Because the business relied on selling their software to customers as a bespoke monolith, there were most likely promises to get extensions to the monolith finished by a certain date. I suspect that the extension and final application were underestimated and like the majority of software projects in the industry finally arrived considerably over the expected budget.

The problem is that monoliths have within themselves undue complexity in terms of logic. An extension of the application is dependent on several factors:

- Comprehensive view of the monolith’s internal working components

- Sufficient translation of new business requirements to technical requirements

- Adapting old components and developing new components

- Dealing with the stress of mixed capable staff

- Unknown impedances in the code, framework and databases

These above are the forces acting on an ageing monolith. At the very beginning of the SDLC, these forces are still there, however the complexity of the code and initial requirements are smaller.

Time to market

Monoliths suffer because of management insistence on delivery to a fixed budget. Of course, it means that due-diligence on the code never takes place and therefore the overall production quality suffers. Developers don’t have time to refactor the code to sufficient quality, code reviews dry up. Morale is destroyed by having to be spoon fed from the political power person during pair-development. It takes longer and longer to write a simple change like adding new field to a HTML form, because architecturally it means trawling though front-end JavaScript framework and altering AJAX, bundling JSON; finding and adapting server-side controllers, changing any database persistent objects and then adding yet another a slap-booty XML configuration to the multitude of LiquiBase scripts. Engineers lose Person-days as you can imagine, because the monolith is so far removed from the Java EE CRUD example that you see in a beginner’s book, and then management wonder what the development team are really archiving? This is the complexity budget, which is sadly, overlooked by management.

Lack of unit tests

Depending of the age of the monolith they demonstrate a shocking minimal degree of unit test coverage. The worst monolith that I ever saw had a ratio of 0.2% test coverage according to SonarQube analysis #6.

The lack of unit tests revealed that obviously time-to-market was a crucial factor in past. Some application monoliths were written before even dependency injection had taken a foot hole in the industry. There were so many static class factory singletons that it made testing incredibly difficult. Although, there was one client that I saw had various degree of success with Power Mock. Even with those monolith that had unit tests, invariably they were not verifying or validating enough outputs against expected inputs. The test were brittle and weak. In some cases, the tests had been deliberately removed and commented out, because I could inspect the version control history log!

Lack of know-how

With dependency injection and modules in general, the industry has shown over the past decade a lack of genuine know-how. It takes a while to design a modular application system effectively and most people need several year’s experience.

We have searched for short cuts in building systems, because of cost-pressure, time-pressure and, of course, monetary-pressure. We have struggled over 25 years attempting to build Object-Oriented applications and systems. It is hardly a surprise that monoliths come into being, because there is plenty of evidence of what not to do: anti-patterns.

Failure to keep up-to-date

As we add more features and functions to a monolithic application and in particular one that we never throwaway, we end up layering complexity on more complexity. It is a bit like having an open wound. The sensible thing would be put an Elastoplast on it, because we think it is the quickest way to alleviate the pain and suffering. However an open wound is not a straightforward cut. It requires antiseptic, cleaning, minor, or sometimes major surgery, and then proper bandages followed by full time it takes for recovery. Software engineers hardly ever get the facilities and support to clean up bad code or change the code smells. It stay infected and becomes worse.

Meanwhile the software development continually finds a brand new way. The Java language, then, introduces annotations in one year. In the following years it introduces functional interfaces, Lambdas and Streams. Yet with a huge mass of monolith with severe complexity and incomprehensibility, it is nearly impossible to use any of those recent features. For one, the management or the stakeholders that fund the monolith and keep the good ship afloat at ship are petrified of the risk of any advancement. For two, politically and often the business model means that they deliberate fail to keep the monolith up to date with technology. And then there is the consideration for Java 9 and Project Jigsaw.

Can a monolith be beautiful?

Recently, I listened to episode 261 of Software Engineering Radio featuring the very opinionated David Heinemeier-Hanson of Ruby on Rails and Basecamp fame.

DHH describes his views on the hype about micro-services oriented architecture (M/SOA). He thought that we were blinded and prone to over-engineer new systems as micro services. Instead, he pointedly described Basecamp as a “majestic monolith” that benefited from a dynamic programming language; and over the past decade optimisations in operating system functionality and CPU performance. DHH argued against going for distributed computing application at the outset, especially in a small setup.

I found his views reassuring for the monolithic application. However, I observed that Basecamp, and I have never seen the code, has been under his complete control since the beginning. Every check-in of code into the version control system was most likely validated. DHH and Jason Fried are unusual, because they are the architects who have stayed with their software. Technical software architects often drop out of coding activities and mostly move on to other software systems and join other companies. Additionally, there is no way to see the “beauty” of proprietary Basecamp without examining the application code, infrastructure and, of course, the people culture at 37 Signals. We have to take their word for it. So while I think a monolith can be magnificent and or even majestic, it is a very tall order to ensure that remains beautiful as time marches on.

There is a severe downside to monoliths in commercial companies. They are not normally open sourced and therefore they cannot subject to independent critical review, not even to the structural engineering, security and compliance types. I suspect that the beauty of a monolith is in the eye of the architectural beholder and therefore it can be used as leverage like a big stick to beat the development staff with it. “This is how it works here, this is what we have and this is how we are going to do it still, in order to get the delivery out of the door for milestone X”. In other words, in their opinion, beauty does not pay the bills, the huge salaries and is unworthy of their customer’s attention. So in the end, we eventually finish up with ugly monoliths and they persist until a critical juncture, which might be business model failure and disruptive entries from the competition.

Symptoms for an ugly Java EE monolith application

A Java EE monolith is unhealthy when it exhibits the following characteristics:

- It was not written from the beginning (5 years ago) as a modular application where modules are self-contained with high cohesion and reduced coupling

- The original architects have left the building and stage; and the current owners have no clue about deep internals

- It is a representation of the political infighting status, managerial power and intrigue

- The owning organisation is resistant to change of the monolith. Worldly external consultants and contractors have a tough time getting management to listen

- There is a distinct lack of unit tests, sometimes with less 5% coverage and integration testing is particularly hard, because agile development falls one or two SCRUM sprints beyond the current one

- It is extremely hard to get around hard code dependencies such as customer detail, test databases and limited environments. In other words, testing the simplest code turns into a nightmare.

- The monolith has severe dependencies on legacy libraries from a decade or more years ago: Struts 1.x, WebWork, Tapestry, Spring Framework 1.x or 2.x and exhibits horrendous XML configuration

- The standard build chain is complicated and takes a very long time

- Even if management suddenly gave the green light to the entire development team today, there would be a huge mountain to climb to adopt Java SE 9 / JDK 9, because the application code has not evolved much beyond Java SE 6 (2007).

All of these problems reflect the company’s origin, the culture and people organisation. We will them in an future episode. So there you have it, Ye Olde Monolith.

[Que horrific laughter from legendary actor Vince Price at the end of Michael Jackson’s Thriller]

+PP+